Indian Peter: A Shameful episode on Aberdeen’s history

In 1743, Aberdeen was not always a safe place for children, as a boy called Peter Williamson found out. Peter had travelled from Aboyne to live with his aunt in the city, but instead, he was kidnapped and taken on board a ship called Planter. He was just ten.

Peter was one of sixty nine children on board. Those who survived the harsh and unsanitary conditions during the voyage were destined to be sold into slavery in the New World. The Planter was not the only ship to carry such a pitiful human cargo from Aberdeen’s harbour. Records held in the city’s archives show that around 700 children, kept in holding houses, were sold at £16 a head, profiting the city’s merchants and magistrates by the equivalent of £1.33 million in today’s currency.

Peter was luckier than many of the other children who survived the eleven week voyage. The ship was wrecked off the coast of Delaware and the children sold in Philadelphia. Peter was bought by Hugo Wilson, from Perth, who had himself once been taken in slavery as a child. Seven years later, when Hugo Wilson died, Peter was a free man. Wilson left his horse, his clothes and £120 to his former slave.

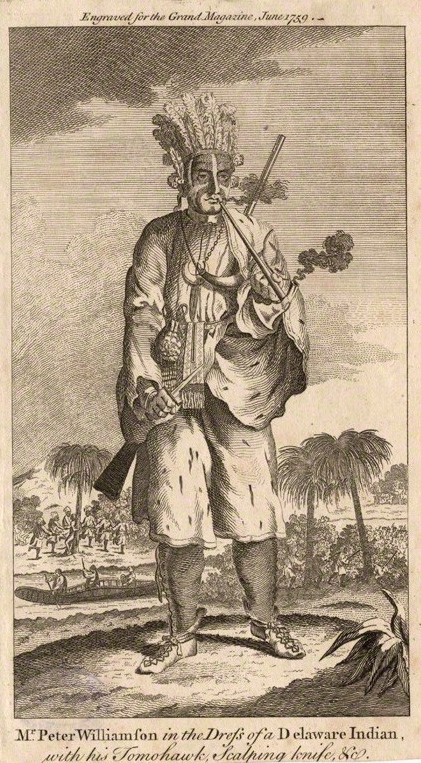

Peter married and became a farmer, but was again taken prisoner in the French and Indian War. He lived as a captive among the Delaware Indians for several months before escaping and joining the colonial militia. In 1756, Peter was sent to England as part of an exchange of military prisoners who had been taken by the French. Nursing a wounded hand, exhausted and almost penniless, Peter found himself in York. Soon his tales of his time living amongst the Native Americans began to draw a crowd and his memoirs were published, selling a thousand copies. By now, he was dressing in an approximation of traditional Native American clothing and demonstrating “Red Indian” culture.

He returned to Aberdeen, in 1758, to be met with libel lawsuits from local magistrates disputing their involvement in his abduction and enslavement. He was found guilty – unsurprisingly, as the same magistrates he had accused, judged the case. He was thrown into prison until he signed a confession and his books were burnt.

Understandably, Peter moved to Edinburgh where he opened up a coffee house, which quickly became popular with the city’s lawyers. They encouraged Peter to take his case to the Court of Session. A ledger showing the profits made from selling the children included an entry with Peter’s name, leading to the previous judgement being overturned. Peter was awarded £200 in damages, plus his legal costs of 100 guineas.

Peter’s next venture was to open a tavern in Parliament Close, then a printing workshop. He even invented a waterproof ink for use on linen and a portable printing press. Ever-resourceful, he followed this with Edinburgh’s first penny post and an independent postal service which was later bought over by the General Post Office.

In his later years, he became known throughout the city as Indian Peter, wearing the garb of the Delaware Indians and even choosing to be buried in his favourite moccasins, fringed leggings, blanket and feathered head-dress.